For organizations moving away from traditional ways of working to Agile ways of working, one of the first questions to answer is,

“How will we communicate the work that needs to get done?”

Most organizations have traditionally used some form of a written Business Requirements Document (BRD). A large and very detailed tome usually researched and written over a long period of time by Business Analysts before being thrown over-the-fence to a development team to read and implement all the requirements over another long period of time.

When these same organizations start to transition to Agile and most commonly, Scrum ways of developing software, the most common way to communicate the work that needs to get done in the Product and Sprint Backlogs are product backlog items (PBIs) written as a User Story.

And, the three most common issues when it comes to User Stories are:

- User stories that have no sign of the “User”

- Everything is a user story even when it’s not

- User stories that read like “War and Peace”

Where’s The User?

One of my family’s favourite activities were the “Where’s Waldo?” series of books and video games. They provided countless hours of fun trying to find Waldo as he and his signature horizontally striped red and white shirt and cap blended into the pictures on every page, effectively camouflaging him. You knew he was there somewhere on the page but you had to find him.

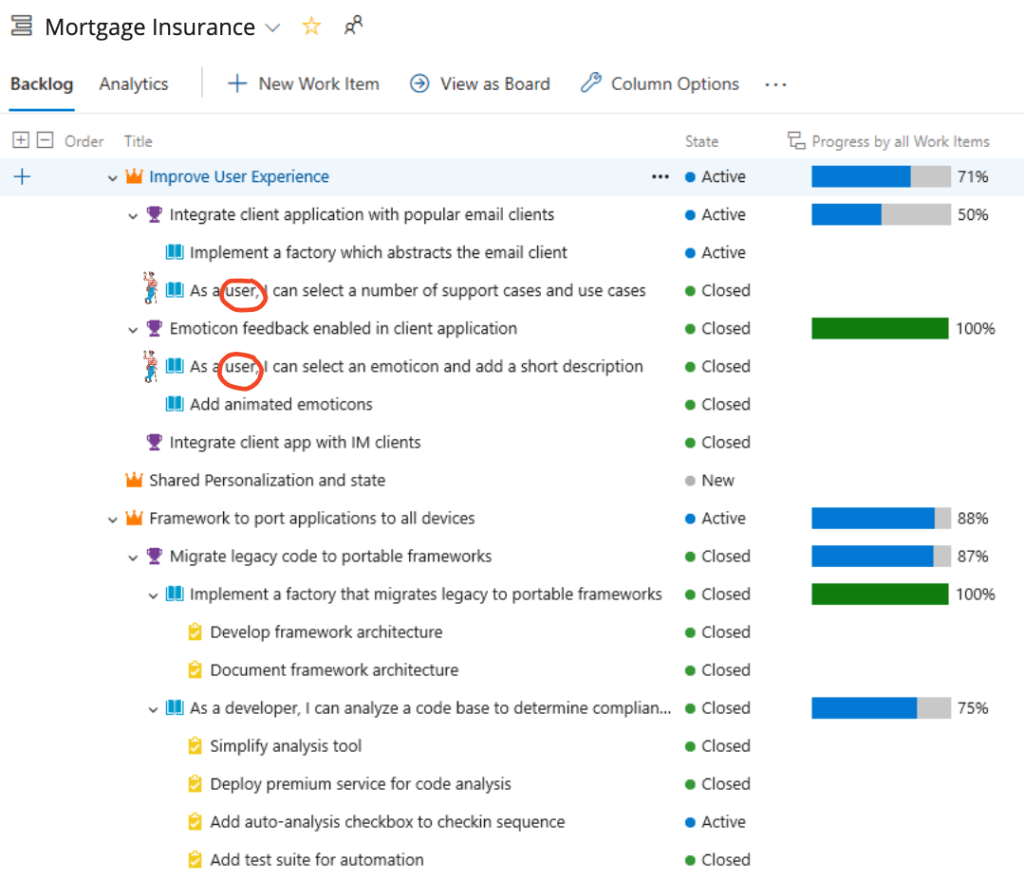

When I review User Stories in a backlog, the first thing I look for is “Who’s the ultimate User?” (ideally, a real human). Trying to answer that question can sometimes feel a lot like playing “Where’s Waldo?”. You know the “user” is there somewhere, you just need to ask enough questions to flush them out.

Often these user stories describe “what” needs to get done but, misses “who” will use the completed work and “why” the user will benefit from the completed work. Most development team members I’ve encountered are happy to just implement the “what” without questioning the “who” or “why”.

Everything Becomes a User Story

The most common type of PBI for Scrum teams is the user story. However, there are many more PBI types including from large to small work items:

- Themes

- Initiatives

- Epics

- Features

- User Story

- Tasks

- Defects

- Risks

- Issues

- Impediments

- Decisions

Many “user stories” that are missing a user can often be recast as a “Task” that is part of a larger user story.

Humongous User Stories

Massive “War and Peace”-like user stories may be a result of trying to decompose an existing voluminous, meticulously detailed BRD into a cut-and-paste collection of large user story puzzle pieces. Each piece incomplete without the whole. Rather than decomposing directly to user stories, each initial User Story may be better recast and reframed as a collection of standalone or independent Epics or Features.

How can one tell whether a user story is too big? In Scrum, if a user story can’t be completed within a sprint so that its value can be demonstrated at the end of the sprint then it’s too big.

Other contributing factors to a larger than necessary user story are the “lost-in-translation” issues in transitioning from a BRD to a User Story. One such issue is the assumption that a user story must communicate ALL the details of what is needed in written form. Most likely a carry-over from trying to cover all the details in a BRD, lest the BRD misses something and has to go through an onerous BRD change request (CR) process!

What’s lost in the translation is the richer multi-channel nature of communications with agile ways of working.

The details of a User Story are not only communicated in written form. The written part of a User Story is only a starting point that communicates the bare essentials of what’s needed such as the “who”, “what” and “why”.

The User Story is an invitation to a deeper, richer, ongoing, and ideally face-to-face conversation with stakeholders like the Product Owner on what’s needed to verify and fill in the gaps not spelled out in the written part of the User Story.

IMHO, this conversational approach to communicating what work needs to be done is one of the biggest missed opportunities when transitioning from a BRD-based to an Agile-based way of developing a product or service.

How does one reduce the size of a user story?

These same conversations with stakeholders will also be key in reducing the size of a user story by splitting or slicing a user story into thin vertical slices of end-to-end business value. The most common splitting patterns being:

- Split by Workflow steps or Paths (e.g. Happy vs Unhappy paths)

- Split by Operations (e.g. Create, Read, Update, Delete (CRUD))

- Split by Data types (e.g. plain text vs. rich text)

- Split by Business Rules (e.g. single user tier vs. multiple user tiers)

- Split by Interface (e.g. web page sections)

Sounds pretty straightforward so, why don’t we do it?

Why does it feel like the practice of Story Splitting has become a forgotten art and remains a hidden gem?

I’ve observed several reasons why:

- Business people want the whole enchilada, all at once. They are 100% certain about what the client needs. They have no patience for iteratively and incrementally splitting those needs. They perceive interim versions as throwaway and a waste of money.

- User stories written like a legal document for fear of missing any details. Any missing pieces or gaps in the story would have to go through an onerous and painful change request process.

- A preference for handoffs over conversation. People don’t take the time to talk with each other. Reinforced by developers who just want to be heads down coding to a spec.

- Poorly written user stories that describe what but not why. Without knowing why a user story is valuable makes splitting the value difficult and arbitrary.

- We don’t know enough about the user. So, we don’t know what they would value in smaller stories.

Even if and when we do agree to split stories, there are several ways it can go wrong:

- Fake “user” stories. The replacement of the ultimate end user with intermediate users leading to self-serving stories. Example: “As a developer of this story, I need to set up an environment so that I can contribute to the story.” Sounds more like a task than a user story.

- Conway’s Law rules. The boundaries of user stories start to resemble the organization’s functional or departmental structure. Example: “As a User, I want a high quality capability so that there are no errors when I use it.”

- Small but not valuable. Story splitting is most effective when the resulting stories are BOTH small and valuable. It’s easy to create small stories. It’s much more difficult to create small AND valuable stories.

- A poorly defined user experience. The user experience often visualized as a journey map can be a great source of inspiration for story splitting patterns. If the user experience is inaccurate or not well understood, any resulting stories may be inaccurate or just plain wrong.

When we do it well, what can go right?

- Common language. We align on what we mean by ‘user’, ‘capabilities’ and ‘value’.

- Visual specifications. Pictures trump words. “Show me” trumps “tell me”.

- Cross collaboration. Conversations bring together and meld multiple perspectives to add life to user stories.

- Everyone writes stories. Amplifies collective ownership and accountability within a team.

- Context setting. Gets everyone on the same page, chapter and book.

- Speed. The time to value and feedback speeds up as the size of stories decrease.

- Safe-to-fail iterative increments. The smaller the story, the smaller the blast radius of any failures. Limiting the impact of any negative consequences and maximizing any learnings towards future stories.

- Reveals conflicting WoWs early. The use of story splitting will quickly expose differences in ways of working in an organization. The sooner differences surface, the sooner they can be resolved.

- Silo vs. Collaborative.

- Big design upfront vs. Just enough design to start.

- Plan and predict — detail oriented vs. Sense and respond — emergent.

- Solution focused vs. Problem focused. Focusing on the what rather than understanding the why.

And wait, there’s more!…

Rediscovering Story Splitting can also be a gateway to another forgotten or rarely used art — Story Mapping.

The practice of Story Mapping is a highly visual way to organize and connect all your split stories. It can be used to:

- Visualize release management

- Preserve and sustain holistic story telling